By Jamye Wooten (January 2018)

“And how are the children?” goes a traditional greeting of the Maasai people of East Africa that places the safety and wellbeing of children at the forefront of all other community matters. The response, “All the children are well,” confirms that the priorities of the community are in order.

The Maasia greeting came to mind a few weeks ago when the children of Baltimore City returned to school from holiday break.

“I’m very, very, very, very, very, very, very cold,” one student stated in response to freezing conditions in Baltimore City Schools. Many children had returned to schools without heat and electricity. Former NFL Player and current Baltimore City School teacher, Aaron Maybin took to social media and stated, “It’s really ridiculous the kind of environment we place our children into and expect them to get an education, I got two classes in one room, kids are freezing, Lights are off. No computers. We’re doing our best but our kids don’t deserve this.”

It’s been two and a half years since the Baltimore Uprisings. Two and a half years since the city erupted in response to state violence and the murder of Freddie Gray. The murder rate is at an all-time high. And the violence that violence created continues; the systemic and structural violence of underdevelopment, displacement, and underfunding of Black communities.

A recent study found that, out of the $670 million budgeted for capital projects in Baltimore (a majority Black city), predominately white neighborhoods were expected to receive twice as much as predominantly Black neighborhoods. The study also showed that richer neighborhoods received nearly three times as much as poorer neighborhoods.

It seems as though the more things change, the more they stay the same. Uprisings gain national attention, talks about equity and race relations come to the forefront, and short-term solutions are offered as an effort to reduce the tension and bring about peace. But this sort of peacemaking doesn’t shift power. It’s more about public relations for the state and the business elite. It is an attempt to silence the cries of the people and return to business as usual.

In 1956, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered a sermon entitled “When Peace Becomes Obnoxious.” Dr. King denounced passive peace that called for Blacks to accept injustice and exploitation. He called us to set aside the type of peacemaking that seeks to keep us quiet or relegates us to second-class citizens.

Dr. King insisted:

If peace means accepting second-class citizenship, I don’t want it.

If peace means keeping my mouth shut in the midst of injustice and evil, I don’t want it.

If peace means being complacently adjusted to a deadening status quo, I don’t want peace.

If peace means a willingness to be exploited economically, dominated politically, humiliated and segregated, I don’t want peace. So in a passive, non-violent manner, we must revolt against this peace.

As I wrote here in Bearings a while back in “Who Has the Right to be Violent,” it is often the church, or what I called “Preacher Pacifiers”, that the state relies on to bring about a false sense of peace. “They dress the wound of my people as though it were not serious. ‘Peace, peace,’ they say, when there is no peace.

The hard fact is that peacemaking it not about making nice. Peacemaking is rooted in equitable power distribution.

“The hard fact is that peacemaking it not about making nice. Peacemaking is rooted in equitable power distribution. It requires putting things in place that will establish long-term peace, justice, and security in hopes of avoiding future conflict. Seeking peace without addressing the imbalance of power is not just. Justice is rooted in love and power. As Dr. King warned us, “Power without love is reckless and abusive, and love without power is sentimental and anemic. Power at its best is love implementing the demands of justice, and justice at its best is power correcting everything that stands against love.”

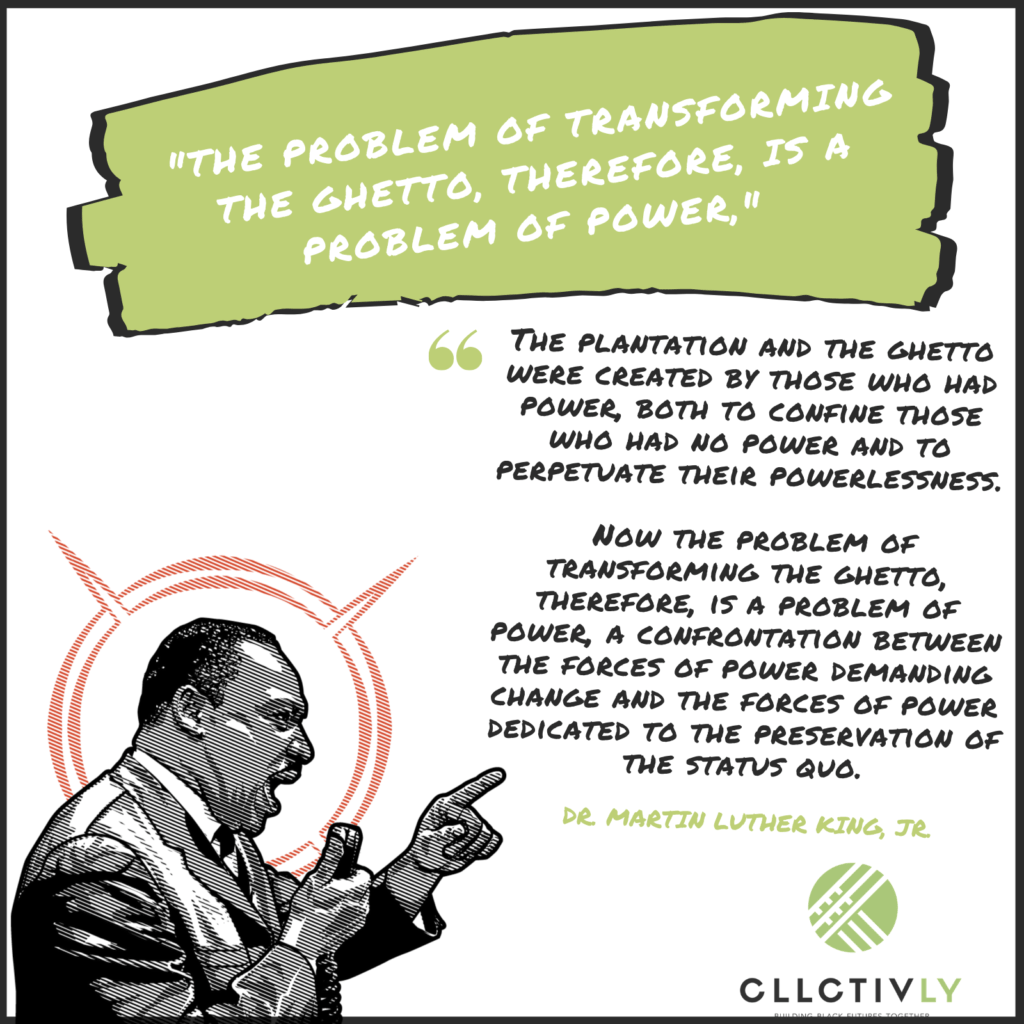

In his 1967 speech “Where Do We Go from Here,” delivered at the 11th Annual Southern Christian Leadership Conference Convention, King cautioned against powerless morality in the face of immoral power, stressing that one of the greatest problems that Blacks faced was their lack of power.

But some 50 years later moral convictions and concerns seem to dominate the discussion in faith-rooted justice spaces. Conversations around peace and justice devoid of power. Power seems to be a discussion that many are uncomfortable having. But the deplorable conditions of Baltimore City Schools and too many Black neighborhoods are a result of power or powerlessness. Again, I turn to Dr. King:

The plantation and the ghetto were created by those who had power, both to confine those who had no power and to perpetuate their powerlessness. Now the problem of transforming the ghetto, therefore, is a problem of power, a confrontation between the forces of power demanding change and the forces of power dedicated to the preserving of the status quo…Now a lot of us are preachers, and all of us have our moral convictions and concerns, and so often we have problems with power. But there is nothing wrong with power if power is used correctly.

He continued,

Now what has happened is that we’ve had it wrong and mixed up in our country, and this has led Negro Americans in the past to seek their goals through love and moral suasion devoid of power, and white Americans to seek their goals through power devoid of love and conscience…It is precisely this collision of immoral power with powerless morality which constitutes the major crisis of our times.

The crisis in Baltimore City and many urban communities across the nation is a result of immoral power and powerless morality. Powerless morality will not lead us to longstanding peace. If peacemaking and moral movements are to have any lasting results we must shift the conversation from feel good discussions around justice and love and begin a discussion around power and equity that is focused on making sure “All the children are well.”